In the early days of the space age, launching and operating a satellite was like driving on an empty Texas racetrack: satellite operators didn’t have to worry about traffic because there weren’t that many other vehicles on the road.

Today, the launch and operation of each satellite is carefully coordinated because some orbits are littered with flat tires from space, abandoned vehicles, loose debris, and, of course, other traffic items.

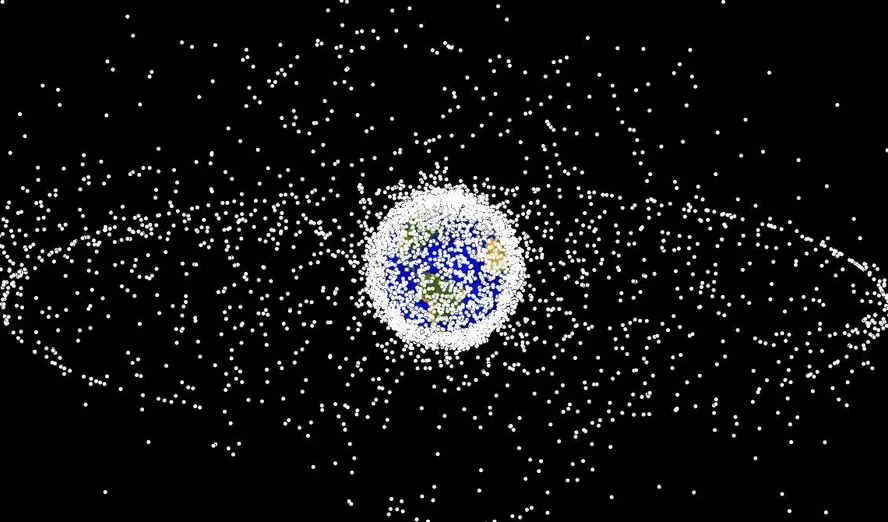

In fact, hundreds of thousands of debris objects larger than one centimetre are scattered throughout the Earth’s orbit. Since orbital speeds can exceed 17,000 miles per hour, even a small grain of sand can be devastating to an active satellite.

Debris thus poses a real threat to our continued use of space in the most favoured orbits.

The growing congestion in space is made worse by the fact that the number of people who rely on space for communications, commerce, weather and navigation is increasing at a dizzying rate.

In December 1994, for example, the satellite television market had 570,000 subscribers. Today, that number has grown to over 35 million.

What is being done to mitigate the risks posed by junk? It depends on who you ask. The risk tolerance of spacefaring nations and commercial space companies usually corresponds to their dependence on space. Those countries or companies that rely heavily on space assets are more likely to be aware of the risk – and take steps to address it.

At the international level, the authoritative body is the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, which has the participation of 76 UN space-faring member states.

All actions related to dealing with the debris problem are either preventive (carried out before launch) (tethering removable lens covers, improving spacecraft shielding) or reactive (manoeuvring satellites to avoid debris, avoiding debris-intensive orbits).

However, if the near-Earth space environment is to be protected, most experts believe that more proactive measures to remove debris are needed, sooner rather than later.

This may be easier said than done. Before proactive measures can be taken, the international community needs to overcome two major obstacles: the development of an effective and economical debris removal technology, and the establishment of an appropriate policy governing the use of that technology.

The ability of the international community to clear the first hurdle will depend largely on the availability of sufficient resources to fulfil the task.

It is almost certain that, with the involvement of world technology leaders and sufficient financial resources, it will be possible to develop and deploy appropriate technology.

The second obstacle poses a greater challenge: designing a policy structure suitable for all spacefaring parties to minimise concerns about the potential misuse of the technology. Without such measures, one country’s rubbish truck may well look like an anti-satellite weapon to another.

Despite these difficulties, the international community must take action to address both challenges by developing the necessary technologies and exploring policy options for their implementation.

Indeed, the policy regime should be the primary concern, as technologies that are developed independently of practical policy considerations may eventually be accepted by the international community.

As the world’s citizens continue to become more dependent on the services provided by space systems, spacefaring nations and businesses should now collectively focus on the risks and policies associated with protecting the space environment.

Ultimately, the difficulty of the space junk problem may not lie in building space junk vehicles, but in getting everyone to agree on how to use it.